Why Asset Tracking Matters in Manufacturing

Losing tools, equipment, and inventory is more than an annoyance. It’s a measurable cost that shows up as downtime, rushed reorders, missed shipments, and lost revenue. That’s why more organizations are investing in asset tracking technologies to improve visibility and keep operations moving. But with so many options, choosing the right system can feel overwhelming.

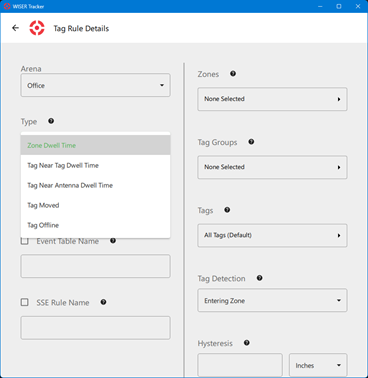

This guide breaks down the most common asset tracking systems used today, with a focus on Real-Time Location Systems (RTLS) and the technologies that power them. RTLS combines hardware and software to continuously track the location of assets, vehicles, work orders, and even people — answering two critical questions: where is something, and when was it there? Many solutions also integrate with ERP, MES, WMS, and other operational platforms to support current business processes.

The RTLS market continues to grow in the manufacturing sector due to increasing demand for automation, asset visibility, and operational efficiency. Manufacturers are looking forward to great opportunities in terms of onshoring and continued demand, but challenges such as tariffs, a shrinking labor force, and global instability, make finding ways to improve efficiency and maintain flexibility paramount. Visibility into process flows are critical for any manufacturer in today’s changing world.

Types of Asset Tracking Technologies

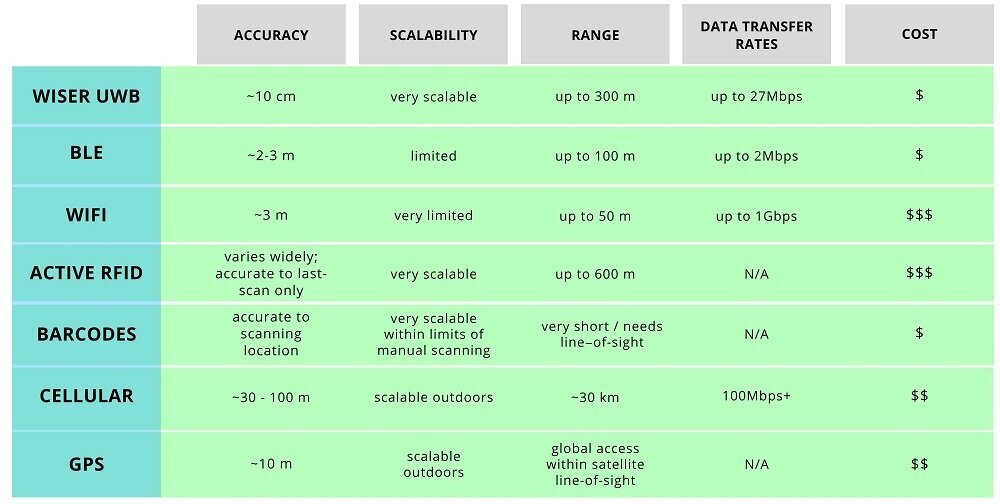

Below, we compare seven core RTLS technologies, which include UWB, BLE, Wi-Fi, RFID, barcodes, cellular, and GNSS (GPS). The guide also touches on several emerging approaches such as computer vision, radar, and sensor fusion. You’ll learn how each technology performs across accuracy, range, scalability, cost, and environmental fit, along with real-world examples to help you choose the best asset tracking technology for your facility.

How to Choose the Right Asset Tracking Technology?

Choosing the right asset tracking technology depends on your end-use. That said, there are a few general parameters that can help you make a smart decision:

- Your desired granularity / accuracy of location data

- Update rates of the tracking technology

- The number of assets being tracked

- The value of assets being tracked and the cost of asset loss

- The physical environment(s) in which you’ll be tracking

- The global / locational area in which you need to track

- Ease of use, including installation and setup

- Costs to purchase and maintain the asset tracking system

Most of these elements vary within the same technologies, but here’s a brief breakdown of some of the most common parameters end-users consider.

1. Ultra-Wideband (UWB) Asset Tracking

With the widescale adoption of Apple Airtags and other consumer UWB tags, ultrawideband has entered the mainstream and is seeing wider acceptance in the manufacturing, healthcare, and other B2B marketplaces. It continues to surpass other tracking technologies in terms of accuracy, scalability, security, and cost-effectiveness. This is why WISER incorporates UWB into its solutions.

Ultra-Wideband (UWB) refers to a technique for transmitting data across a broad section of the radio spectrum. It achieves this by emitting short pulses with low power output over a significant bandwidth. Essentially, UWB is an efficient, low-power method for sending a substantial amount of data.

Traditional Bluetooth and Wi-Fi RTLS systems, which typically rely on Received Signal Strength Indications (RSSI) can suffer in accuracy in indoor cluttered environments due to mutli-path reflections. UWB on the other hand, is good at disregarding reflected signals. This is what makes UWB work so well in environments with a lot of walls, like hospitals, or many metal reflective surfaces like manufacturing plants.

Ultra-Wideband (UWB) continues to expand rapidly in the automotive sector. It powers advanced features such as secure keyless entry, child presence detection, and in-cabin gesture sensing. UWB chips are also becoming standard in new smartphones such as the Google Pixel series, Samsung Galaxy series, and Apple iPhone. It has been an exciting year for innovation, as next-generation UWB chipsets from NXP, Spark Microsystems, and Qorvo deliver even higher accuracy and support for true 3D positioning, enabling improved vertical as well as horizontal tracking. In terms of standardization, in addition to ongoing work by the FiRa Consortium and Omlox, the upcoming IEEE 802.15.4ab amendment expected will further enhance interoperability and performance for next-generation UWB applications.

Together, these advances signal that UWB is achieving even stronger performance in real environments, with lower power, more secure designs, tighter integration, and broader interoperability.

Advantages

- Data transmission through many walls and obstacles

- Non-interference with most other RF devices

- Unique radio signatures and improved ability to avoid multipath propagation

- Low power

- Enables high location accuracy—often within inches

These benefits make UWB ideal for locating and tracking in heavy industry and GPS-occluded environments. It’s also ideal for high-value assets or situations where inaccuracy poses considerable risks—such as safety, security, and healthcare applications.

UWB’s ability to operate without a line-of-sight between devices gives it quite a bit of flexibility. This is key for factories where tracking systems must operate around metal and other reflective surfaces. Here, UWB’s unique radio signature is a natural deterrent to multipath propagation. It also works well in envirnoments with many small rooms and few open spaces, like hospitals.

Power efficiency is a key advantage for UWB. For tracking solutions like WISER’s, this allows tracking devices to last for years at a time without recharging or replacing batteries.

Disadvantages

The biggest disadvantage for UWB are its infrastructure needs. For instance, GPS is essentially ubiquitous for outdoor location, and WiFi networks are easy to access across much of the populated globe. UWB, on the other hand, often requires deployment of new, unique hardware across a given tracking area.

Another possible disadvantage is that many UWB applications rely on precise time-syncing between devices. This can complicate the installation process, which is often a large cost for asset tracking technologies. It’s not uncommon for UWB solutions to require laser measurements between stationary devices, and this gets cumbersome and pricey in a hurry.

Fortunately, this obstacle isn’t insurmountable. Solutions like WISER’s feature a wireless auto-calibration process. This means that end-users don’t have to measure with a ruler, let alone a laser. This makes the installation process quick, efficient, and inexpensive. In addition WISER devices do not need line-of-sight like other UWB RTLS solutions.

Where It Works Best

Ultra-Wideband is the preferred solution in environments where high accuracy and real-time updates are non-negotiable. From metal-filled manufacturing floors and hospital wards to autonomous robotics and critical infrastructure, UWB provides the reliability and precision that Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, or cellular technologies cannot match.

Some modern UWB systems can now provide seamless indoor–outdoor tracking across controlled campuses and yards. By deploying weatherized antenna devices and appropriate backhaul, the same UWB tags deliver sub-foot level accuracy as assets move from factory floors or hospital interiors to adjacent loading docks, parking areas, or outdoor storage. This eliminates gaps that often occur when switching between BLE, Wi-Fi, and GPS.

Case Study: Work-in-Progress Tracking with WISER.

2. Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Asset Tracking

Bluetooth is one of the most common technologies used for indoor positioning applications like asset tracking. The technology has been available for years, and its low power consumption gives it a nice edge over other older solutions like WiFi and GPS.

BLE systems usually establish their own wireless networks with a combination of Beacon and Hub devices. Many BLE solutions can incorporate existing devices such as smartphones. This can simplify the implementation, especially for applications using mobile devices.

In recent years, newer enhancements like Bluetooth channel sounding (CS) using Phase-Based Ranging (PBR) and/or Round-Trip Time (RTT) are improving BLE’s position accuracy significantly. This makes BLE more competitive with UWB in certain scenarios. However, channel sounding solutions in its current form has limited scalability and fairly short ranges.

Advantages

- Low power consumption

- Relatively inexpensive devices

- Potential for cross-functionality with common consumer devices

- Accurate up to a few meters

The ability to use mobile devices as roaming hubs makes BLE a particularly common technology for consumer applications. It’s also a common tracking solution for indoor environments like shopping malls and hospitals.

Like UWB, BLE systems typically don’t require any manual scanning or searching. Using Received Signal Strength Indications (RSSI), BLE can determine proximal asset locations more or less as objects move. Newer developments in BLE can also enable localization via direction finding methods.

Disadvantages

- Scalability and Volume

- Risk of wireless interference

- Requires a high density of transmitters

- Inaccuracy in reflective or highly active environments like factories or refineries

- Security vulnerabilities

Scalability and tag volume are big disadvantages of BLE. There’s a decent chance of signal interference, since so many devices already compete for space in the same part of the radio spectrum as BLE. This may result in lost coverage, dropped datapoints, and reduced speed. As more tags are tracked in a given area, the risk of signal interference increases, reducing reliability.

Beacon systems such as BLE employs often require a high number of networked devices. Standard BLE antennas normally has a range of 20 meters which can be a problem in areas with tall ceilings like factories. When higher numbers of antennas are needed, hardware costs grow even before installation and maintenance fees.

BLE devices face operational limits in some environments. BLE solutions don’t function particularly well around metal or reflective surfaces. Some systems come with workarounds for this, such as additional WiFi-connected devices, but this can cause other problems like added network latency and interference, both which limit scalability. Active environments with many moving parts are also a challenge for technologies like BLE, because RSSI methods can be thrown off by temporary obstacles moving in and out of the setting.

Finally, Bluetooth solutions generally face numerous security risks. One of the biggest security obstacles is the wide adoption of Bluetooth technologies, making everything from phones and keys to headphones and keyboards susceptible to attacks using similar protocols. The developing Bluetooth Channel Surfing technology is incorporating anti-spoofing technologies to improve security.

Where it works best

Bluetooth Low Energy is the ideal choice for deployments where cost efficiency, long battery life, and easy integration with consumer devices outweigh the need for foot-level precision. Also in environments where ceilings are lower, a smaller number of tagged items are needed, and large ranges are less important, BLE handles general location tracking well. From retail and healthcare to smart buildings and mixed-technology systems, BLE offers a sweet spot of affordability, scalability, and acceptable accuracy

3. Wi-Fi–Based Asset Tracking

WiFi is a communication tool that is basically everywhere to support internet access and intranet connectivity through the office and home. Because of its ubiquitous nature, many facilities have adopted it for tracking.

Like BLE, WiFi primarily uses RSSI techniques to locate and track assets. This includes using historical RSSI in a method called fingerprinting. As with BLE and UWB, some WiFi solutions also use AoA and ToF measurements, though these usually require specialized equipment with a more complex setup and calibration beforehand.

Over the last few years, WiFi has advanced significantly with the WiFi 6 and now 7 standards. With the arrival of WiFi 6E and WiFi 7, WiFi-based localization is becoming more compelling for asset tracking. New features like 320 MHz channels, 4K-QAM modulation, and Multi-Link Operation (MLO) allow devices to more reliably spread traffic across multiple bands and mitigate interference. Meanwhile, support for Fine Timing Measurement (FTM) / RTT ranging in modern WiFi chipsets enables decimeter-level distance estimation. Combined with smarter AI/ML algorithms and fingerprinting techniques, WiFi localization is now stronger than ever. That said, it still typically offers lower precision than UWB in harsh or high-accuracy use cases. Further, power consumption is still much higher than UWB tags. This has the side effect of either requiring frequent recharging of the tags, or the tags need to be connected to an independent power source. Calibration also remains an important consideration.

Advantages

- High data rate throughput

- Large wireless range

- Potential to work with many different WiFi-enabled devices

- Operability with existing WiFi networks lowering installation costs

- WiFi standardization simplifies development and interoperability

Businesses and individuals already use WiFi to transmit data of every conceivable kind. This means that WiFi tracking solutions often need fewer bridging mechanisms for the data.

Like BLE and UWB, WiFi is better suited for localized tracking than global. WiFi’s near omnipresence in business settings is especially advantageous for small-scale projects with only a few key assets, since it could mean that end-users don’t need additional network infrastructure to begin tracking.

Notably, it does take some infrastructure adjustments to move from a legacy WiFi 4/5 or even a WiFi 6 system to a WiFi 7 system. Upgrading to Wi-Fi 6/7 for asset tracking typically requires new access points and client devices that support Fine Timing Measurement (FTM/RTT) and the latest frequency bands. While legacy WiFi clients can still connect for basic data, true next-generation location accuracy depends on compatible hardware and RTLS software. Existing Ethernet cabling may suffice, but multi-gigabit backhaul and PoE++ are recommended to fully realize Wi-Fi 7’s potential.

Disadvantages

- Lack of scalability

- Inaccuracy

- High power consumption, frequent charging, or access to power for tags

- Congestion of existing WiFi networks

- Security risks

Inaccuracy and unreliability are common issues in wireless tech using RSSI—like BLE and WiFi. It’s possible to get positioning within a few meters, but moving objects and other obstacles often throw precision off significantly. This limits WiFi’s use in asset tracking. It’s also part of why WiFi solutions are difficult to scale.

Another scalability challenge is the limit to WiFi spectrum space and access points. In this sense, WiFi’s ubiquity is often a two-edged sword.

This gets even more problematic if asset tracking solutions operate on the same wireless networks as internal communications or other key operations. First of all, network congestion is common enough without trying to add dozens or hundreds of real-time location reports. Secondly, most current WiFi deployments won’t have ideal positioning to support an RTLS or asset tracking application.

WiFi 6 and 7 substantially reduce the interference and latency challenges that historically limited the simultaneous use of WiFi for communication and real-time location tracking. Features such as OFDMA, 6 GHz spectrum, and Multi-Link Operation allow location packets and high-bandwidth traffic to coexist with far less congestion. However, Wi-Fi remains a shared medium: careful network design and client compatibility are still essential to maintain reliable performance under heavy load

The widespread use of WiFi does make it more prone to attack. WiFi 6 and 7 significantly improve wireless security by mandating WPA3 encryption, supporting Opportunistic Wireless Encryption, and protecting management frames. However, they do not make WiFi impervious to attack. Proper configuration, strong authentication policies, and regular firmware updates remain critical to maintaining a secure asset tracking environment.

Where It Works Best

WiFi 6/7 is the ideal solution in environments that already maintain a dense enterprise Wi-Fi network and require meter-level accuracy alongside high data throughput. Hospitals, offices, smart campuses, and mixed indoor-outdoor logistics facilities can achieve cost-effective location tracking with minimal new hardware while continuing to support high-bandwidth applications on the same infrastructure.

Legacy Asset Tracking Technologies Still Used

4. Barcode Asset Tracking Barcode Asset Tracking (Including QR Codes)

Barcodes are absolutely everywhere throughout the retail and commercial world. They are a great way to cheaply identify any item. You can check a database for information tied to that code with a simple click of a barcode scanner. Barcodes remain the lowest-cost option for simple, line-of-sight identification tasks like retail checkout or shipping labels.

While RFID, which is described below, most often uses doorway readers, barcode scanners typically require a human operator. The downside is that barcodes need to be scanned more or less individually. On top of that, the typical scanning range is only a few inches, meaning you need to be very close to successfully make that scan.

Advantages

- Very inexpensive

- Extremely small and lightweight; A literal sticker

- Can account for massive numbers of assets with no theoretical limit on quantity

- Barcode scanners are typically much more affordable than RFID scanners

Disadvantages

- Requires labor-intensive manual scanning and searching

- Scanning requires line-of-sight and often very short range

- Dependent on data from last point-of-scan

- Prone to human error like missed and erroneous scans

- Often requires expensive software components for inventory management

Barcodes don’t show location, let alone real-time status. What they do show is identification at the last recorded scan. This means scanning needs to be recorded with some form of location data to actually know where assets are.

Limited as barcodes are, they have more than shown their value in the 70 years since their invention. For applications with massive numbers of low-value assets, it’s hard to find a more feasible system and WISER encourages pairing its RTLS system with RFID. Furthermore, WISER laser-engraves a barcode on every tag and includes a barcode scanning feature in its app. This way users can then simply scan the tag and then the item information, work order, or other scannable information to quickly link the physical tag to the digital information about the item. It’s a great example of using older and newer technology together.

5. RFID Asset Tracking: Passive, Active, and Hybrid Systems

For legacy tracking systems, Radio-frequency identification (RFID) is the next step in terms of common usage. Versus the simple Barcode, RFID is preferred when you need speed, automation, bulk scanning, or ruggedness — such as in logistics, healthcare, or manufacturing. In practice, many organizations use both: barcodes for everyday scanning, and RFID for automated asset tracking.

Most RFID systems operate in unlicensed ISM (Industrial, Scientific, and Medical) bands, most notably 13.56 MHz for HF RFID and 860–960 MHz for UHF RFID. These globally available frequencies make RFID inexpensive and widely deployable, though they can also be congested since they are unlicensed.

Over recent years, RAIN (RAdio Frequency IdentificatioN) RFID has become a standard While UHF RFID refers to any RFID system operating in the 860–960 MHz band, RAIN RFID specifically denotes passive UHF RFID solutions that comply with EPC Gen2v2/ISO 18000-63 and are supported by the RAIN Alliance. In practice, RAIN has become the dominant ecosystem for UHF deployments in retail, logistics, and healthcare, ensuring interoperability and large-scale adoption.

RFID systems primarily function through a combination of electromagnetic readers and tags. Tags contain data that can be read by both stationary and handheld RFID readers. These readers, often called interrogators, detect the presence of tags. While primarily identifying the tags being scanned, readers can also provide additional data. For instance, a fixed-location reader, like a doorway scanner, can log the specific time an RFID tag crosses the threshold, recording its location at that moment. Both stationary and handheld scanners are useful for inventory processes, security checks, and similar tasks.

The primary goal of an RFID system is to determine which tags are within the range of which readers, often boiling down to a binary question: is the tag detectable or not? The range largely depends on the type of reader used and the techniques employed to interrogate the tag.

Advantages

- Very small and unobtrusive tags—especially passive ones

- Long device life

- Low cost for tags

- Small radio signature

RFID systems often offer a multitude of tag form factors, which enable them to be used on many kinds of assets. RFID tags can identify large objects like vehicles and heavy machinery, but can even be embedded inside hand tools. The low cost of passive RFID tags makes it feasible to track a high quantity of objects as well.

Many players are combining RFID into other technologies such as Bluetooth and UWB to take advantage of the cheaper cost of RFID for some items as well as the accuracy of BLE and UWB for others.

Hybrid tags combine the strengths of RFID’s low-cost identification with BLE or UWB’s real-time location accuracy. In practice, this means a single tag can be scanned passively at choke points (using RFID) while also broadcasting active signals for continuous positioning. These dual-function devices are increasingly used in logistics, manufacturing, and healthcare where organizations need both scalable inventory visibility and precise real-time tracking.

Disadvantages

- Variability of precision

- High cost of readers

- Complex system installations, often requiring manual scans

- Wireless signals are often easy to intercept

- No true location data

- Battery hassles with large deployments of active tags

RFID tag-reading systems, while valuable, come with certain limitations. They can be cumbersome due to the need for manual scans and often imprecise in their data accuracy. Typically, RFID can indicate whether an asset is present, but defining “present” can be problematic. Missed scans during object movement can result in inaccurate asset tracking, potentially leading to irretrievably lost items.

The most robust RFID solutions often involve strategically placing multiple readers or positioning low-range readers at choke points, such as doorways. While effective, these methods can be costly to install and adjust, given the high expense of the readers themselves. Other approaches, like using roaming readers to increase location precision, add complexity and may require recurring manual labor.

Despite these efforts, end-users typically only know if the RFID tag is near the reader or where it was last successfully scanned. This level of information might suffice for many inventory systems, but it doesn’t provide real-time location tracking and won’t help find a lost asset immediately.

Where It Works Best

RFID works best in high-volume, low-cost identification scenarios such as retail, logistics, and healthcare, especially at choke points, during audits, or where line-of-sight scanning is impractical. Its low tag cost and ability to scan hundreds of items at once make it ideal for inventory accuracy and supply chain visibility, though it is less suited for real-time, high-precision location tracking.

Some Special RFID Technologies Important for RTLS

RFID includes both passive and active systems, each using different methods for communication between tags and readers. Passive RFID tags, which have no internal power source, draw energy from the reader’s signal to transmit their data. This makes them inexpensive and long-lasting, though their read range is limited. Active RFID systems, by contrast, contain a built-in power source that enables much longer read distances—sometimes up to hundreds of feet—but at a higher cost per tag. A third option, known as semi-passive or battery-assisted passive RFID, uses an onboard battery to power the chip but still depends on the reader’s signal to communicate, striking a balance between range and cost.

In recent years, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), Wi-Fi, and Ultra-Wideband (UWB) technologies have begun to surpass active RFID in popularity for real-time location and asset-tracking applications, largely due to their higher accuracy, faster data rates, and easier integration with existing networks. However, RFID continues to evolve. One notable advancement is the pairing of RAIN RFID with phased-array antennas. This innovative approach enables users to leverage the low cost and scalability of passive RFID tags while achieving a degree of real-time location awareness. These systems can perform well in environments with lower ceilings and open floor plans, though read performance may be affected when tags are obstructed or located too far from the antennas.

Case Study: Tool-tracking with passive RFID and UWB.

Outdoor Asset Tracking Technologies

Cellular Tracking and GNSS are really the grandfathers of location tracking and logistics. While these technologies are often the cornerstone of logistics, in this article we’re going to focus more on their role in RTLS or the management of a pre-defined yard area or the outside skirt around a building.

6. Cellular Asset Tracking for Long-Range Visibility

Cellular asset tracking can determine the state, city, or even neighborhood of an object from many miles away. It is basically the same as attaching a simple cellular phone to a device and tracking it. It doesn’t get very precise, though.

While pure cellular tracking was once used for outdoor visibility, the cost and power profile of GNSS chips have dropped so far that nearly all modern solutions now combine GNSS with cellular. GNSS provides slot-level yard accuracy, while cellular delivers the communication channel. Pure cellular tracking persists only in ultra-low-cost or coarse geofencing applications. You might still see it used for fleet tracking, cargo container tracking, or agricultural/construction equipment.

For our world of Real Time Location Tracking where accuracy is important, cellular is almost universally paired with GNSS (GPS) for outdoor tracking.

Advantages

- Long range

- Near global reach

The clearest advantage of Cellular asset tracking is that it’s often usable from the point of origin all the way to the point of delivery without tapping into additional technologies.

Disadvantages

- Very high power consumption

- Slower update rates—typically in order to conserve power

- Risk of dead spots in obscure signal areas

- End-users rely on a third party for coverage and can’t repair the system in cases of lost coverage

- Limited use in indoor or underground locations

- Low tracking accuracy

While Cellular works well in a variety of global logistics applications, it has its limitations. Power consumption is high on the list. Just as cellphones typically require a daily recharge, most Cellular asset tracking solutions need to recharge or replace batteries after just a few trips. This contrasts with the years-long or decades-long lifespans of some more localized asset tracking devices.

Inaccuracy is another top limitation with Cellular. It primarily works by trilateration of signals from cell towers, so the math is dealing with big numbers and big error margins in even the best cases. Tracking accuracy usually peaks at 30 meters or so and can be much less in other cases.

Cellular providers are increasingly partnering with satellite networks to create hybrid cellular–satellite solutions. Initiatives such as Starlink’s Direct-to-Cell service and Amazon’s Kuiper project extend coverage into areas where terrestrial networks are limited or unavailable. For industries with remote operations , such as, agriculture, energy, mining, or construction in rural regions , these hybrids can ensure continuous connectivity for communication and asset tracking. While still in the early stages of deployment, they represent a promising path toward bridging coverage gaps in the global tracking ecosystem. Accuracy is another top limitation with Cellular. It primarily works by trilateration of signals from cell towers, so the math is dealing with big numbers and big error margins in even the best cases. Tracking accuracy usually peaks at 30 meters or so and can be much less in other cases.

7. GNSS (GPS) Asset Tracking for Outdoor Location Tracking

Despite what you might see in spy movies, global navigational satellite systems (GNSS) are not a magic bullet for real-time location. Examples like the United States’ GPS are, however, some of the most widely-used tracking technologies in the world today.

GPS depends on knowing the locations of in-orbit satellites and synchronizing their clocks precisely. This constellation of GNSS satellites include the U.S. GPS, Europe’s Galileo, Russia’s GLONASS, and China’s BeiDou systems which are continuously broadcasting timing signals that your GNSS chip can pick up and use to calculate your position. Unlike cellular there is no monthly subscription to use this network. You just have to pay for the chip that is in your phone and then of course all the software to turn all that coordinate data into useful information like a friendly blue line heading back to your house.

In the RTLS world, GNSS solutions can be used within defined outdoor areas in applications for yard management or tracking materials stored outside a building.

Advantages

- Global visibility for tracked assets

- Wide availability of GPS signals

- Large library of GPS tracking applications

- GPS antenna integration into many professional and consumer devices

Like WiFi and barcodes, one of GPS’s biggest advantages is simply that people recognize it. They might complain about it, but that’s usually evidence that they’ve used GPS—even that they rely on it. And, for the most part, people trust its reliability. Additionally, many organizations work hard to make it even more reliable.

Disadvantages

- Requires line-of-sight with satellites

- End-users cannot repair or adjust the space or control segments

- High power consumption

- Low accuracy in most cases

- Interruptions in signal due to solar storms, spoofing, or other interference can be an issue

The primary drawback of GPS asset tracking is its reliance on a clear line-of-sight with multiple satellites. This dependency makes GPS unreliable in metropolitan areas, behind mountains, and especially underground. Additionally, GPS signals are often unstable or unusable inside most buildings.

For industrial applications, GNSS outages aren’t usually about the entire system going offline, but local interference, jamming, or signal blockage. That’s why modern yard management, logistics, and construction systems rely on hybrid designs: GNSS for outdoor accuracy, with fallback to UWB, BLE, RFID, or dead-reckoning sensors when satellites aren’t reliable. In critical sectors, such as aviation, defense, and energy, redundancy is not optional — it’s required.

Accuracy is another limitation, with GPS generally providing precision within 5-10 meters. Achieving higher accuracy requires a complex and expensive differential GPS system. Although car navigation apps may appear more precise due to front-end adjustments of the actual data, this can sometimes result in inaccuracies, such as displaying your location on a parallel road. While this level of accuracy is usually sufficient for tracking vehicles and other large assets, it may not be suitable for smaller assets.

Given these challenges, businesses must consider the limitations of GPS asset tracking and evaluate whether it meets their specific needs, particularly for smaller or indoor assets.

In terms of advancements, high-precision GNSS using PPP (Precise Point Positioning) and RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) corrections has moved from niche to mainstream in sectors like surveying, agriculture, and construction, where centimeter accuracy is critical. Thanks to cheap multi-frequency chipsets and global correction services, sub-meter accuracy is now increasingly available. Market adoption is accelerating, but cost, subscription requirements, and environmental limitations mean most industrial users still deploy it selectively.

Where it Works Best

GNSS works best outdoors in open areas — from yard management and fleet tracking to agriculture, construction, and aviation. It provides global visibility without additional infrastructure, making it ideal for vehicles, containers, and large equipment. However, GNSS is less effective indoors, in dense urban environments, or in applications where battery life is critical, which is why hybrid solutions (GNSS + cellular, or GNSS with UWB/BLE indoors) are common.

Less common asset tracking technologies

Ultrasonic Asset Tracking

Ultrasonic positioning isn’t new. It’s based on the same echolocation principles used by bats and dolphins. However, it remains a niche approach within modern RTLS. These systems measure the time of flight of sound waves between transmitters and receivers to determine precise distances, often achieving centimeter-level accuracy in quiet, controlled environments. Still, their use in industrial settings is limited. Ultrasonic signals are easily blocked by physical obstacles, air currents, and background noise. As a result, ultrasonic RTLS is now primarily used in specialized applications such as hospitals, clean rooms, and laboratories, or as a complementary technology within hybrid systems that combine sound and radio signals for added precision.

Radar-Based Asset Tracking

Like other technologies originally developed for defense applications, radar has found new uses in civilian and industrial settings. Modern radar systems, particularly those using millimeter-wave (mmWave) frequencies such as 60 GHz and 77 GHz, provide highly sensitive motion detection and proximity sensing capabilities. When paired with known facility layouts or fused with other sensors, radar can help detect the movement of people or vehicles. However, radar alone is rarely used for asset tracking. It cannot easily identify individual objects or associate unique IDs with detected motion. Most radar systems also require line-of-sight or near-line-of-sight operation, and high precision often demands large or dense antenna arrays, which add cost and complexity. For these reasons, radar today is primarily used as a complementary technology—enhancing safety, occupancy monitoring, and automation systems—rather than as a standalone RTLS solution.

Infrared (IR) systems, which also rely on line-of-sight, continue to serve in presence and imaging applications but are limited in scope for true location tracking. Their focus on motion or heat signatures, rather than identification, makes them less effective in large or complex industrial environments.

Computer Vision for Asset Tracking

At a high level, computer vision refers to the ways in which computers make sense of images. This can include facial or object recognition, motion estimation, and other methods for analyzing video or still images. This requires cameras—potentially a lot of them—and a line-of-sight. Computer vision solutions might also have their own lighting requirements, further adding to setup complexity and overall cost. It also depends on a large amount of processing power and high data throughput compared to other asset tracking systems. Computer vision, however, can be very precise within controlled parameters and can use inexpensive tags like QR codes. Computer vision systems such as facial recognition can also handle limited object identification without any physical tagging.

In recent years, advances in edge AI and machine-learning models have made computer vision far more practical. Modern systems can now identify and track assets or people in real time using inexpensive cameras, sometimes aided by visual markers such as QR codes. In many facilities, vision systems are integrated with UWB, BLE, or RFID data to combine visual context with precise location and identification. The result is greater situational awareness which supports automation, safety analytics, and real-time digital twins.

Integrating Asset Tracking Technologies into a Complete RTLS Solution

Few, if any, of these asset tracking technologies are mutually exclusive. With a bit of creativity, you can mix, match, and combine them in numerous ways. For instance, WISER’s solution integrates UWB with barcodes to enhance tracking capabilities.

It’s crucial to ensure that the asset tracking technology aligns with your specific use case. For example, tracking items in a grocery store probably doesn’t require GPS, whereas locating $100K worth of copper on a factory floor might need more than just a barcode.

If you’re unsure which asset tracking technologies to use, let the specific end-use guide your decision. This approach will help you select the most effective and efficient solution for your needs.

(original post by Stephen Taylor; Last updated January 2026 by Liz Hollar)